In my last post I spent awhile talking about the growth of amateur culture from a fairly niche sort of thing to a broader - and far more accessible - phenomenon. Considering the extent to which we've been throwing terms like "MySpace Generation" or "Youtube Generation" around in the last several years I think it's pretty safe to suggest that the Net might have had something to do with this. It makes sense to suggest that the Net is going to shape the interpretation and presentation of even traditionally-academic subjects: it's utterly ubiquitous in the developed world these days, and large swathes of its original incarnation developed out of academia in the first place anyway.

In my last post I spent awhile talking about the growth of amateur culture from a fairly niche sort of thing to a broader - and far more accessible - phenomenon. Considering the extent to which we've been throwing terms like "MySpace Generation" or "Youtube Generation" around in the last several years I think it's pretty safe to suggest that the Net might have had something to do with this. It makes sense to suggest that the Net is going to shape the interpretation and presentation of even traditionally-academic subjects: it's utterly ubiquitous in the developed world these days, and large swathes of its original incarnation developed out of academia in the first place anyway.While it's weird to think so these days, with the Internet's recent proliferation of just about any kind of frivolity, inaccuracy, or Thing Man Was Not Meant To See, the Internet was once, at its heart, a fundamentally academic institution. Its culture was largely that of the American computer-science student community, with rhythms organized around the academic year. Many still use the term "September that Never Ended" to describe all time since September 1993 - referring to the annual influx of newbies with little awareness of proper netiquette which became an unending flood that fall - and speak with almost a religious hope of the prophesied October 1, 1994, which has yet to arrive. "What's your major?" was a question equivalent to "what's your sign?" and so on.

While it's somewhat obvious that the bulk of online culture is no longer centered around those kinds of patterns, a core of them is still around and at least influences a large portion of the Net. Large swathes of the parts of the Net with a useful signal-to-noise ratio have much in common with the Net's original large-scale discussion system, Usenet, before its collapse to in the mid-1990s. Usenet, and its current successors[1], had a combination of an anything-goes approach subject-wise and a lack of any barriers to participation beyond simple access to the network in the first place. The results varied from the completely silly (such as most of the thousands of groups in the "alternate" hierarchy[2]) to general-interest groups (such as rec.pets.cats), to artistic communities (such as alt.fiction.original, which a couple of friends and I created in the mid-90s as an escape from the ubiquity of horrific fanfiction) to more academic topics (such as sci.archaeology).

Unless someone was already known by name otherwise - a known scholar in a given field, or one of the various alpha geeks of the Internet at the time[3] - there were no clear

credentials or pecking orders to go by other than reputations as established in a given forum. It resulted in an odd sort of situation where someone using a real name and some postnominals and someone else with an elaborate and obvious pseudonym would generally end up on an equal footing in discussion from the get-go and diverge based on shown competence alone. (As an example, someone I knew some years back, who wound up hugely respected in the spam-fighting field, was - and to my knowledge, still is - known only as "Windigo the Feral.") While a lot of people were, and still are, dismayed at the potential for this kind of anonymity, many others found (and find) it liberating.

credentials or pecking orders to go by other than reputations as established in a given forum. It resulted in an odd sort of situation where someone using a real name and some postnominals and someone else with an elaborate and obvious pseudonym would generally end up on an equal footing in discussion from the get-go and diverge based on shown competence alone. (As an example, someone I knew some years back, who wound up hugely respected in the spam-fighting field, was - and to my knowledge, still is - known only as "Windigo the Feral.") While a lot of people were, and still are, dismayed at the potential for this kind of anonymity, many others found (and find) it liberating.This kind of digital culture - gleefully eccentric, technically minded, generally libertarian and explicitly meritocratic - and its descendants have had a tremendous influence on a lot of digital-humanities concepts, between their broader impacts on digital culture in general and the fact that a lot of people working in the digital humanities tend to have strong computing backgrounds. This kind of community was the one which is the source of the whole open source movement, the source of any number of tools I've mentioned on this blog. Zotero, Blender, Celestia, and Freemind are just four examples that immediately come to mind, and each is a program which came out of this movement which I've managed to turn to one historical purpose or another at least once this year. Each of those already exists as commercial software, but they have the little advantage of being free. When compared to Endnote ($300), Lightwave ($1100 - thousands of dollars cheaper than when I last checked!), Voyager 4 ($200) or Mind Manager Pro ($350) , I know full well where my preferences are going to lie - particularly since both sets of software are often similar or identical in terms of capabilities, even when correcting for open-source software's tendency towards lousy interfaces. There are moves to unify these sorts of things towards educational purposes, even in the realm of physical computers themselves. And to make it even better, should I feel moved to and have the capabilities I can, as Dr. Turkel put it, feel free to fix anything that is bugging me.

This sort of attitude - that I (and you!) should have a say in what's going on if we're able to do so in a competent manner - is, I find, a healthy one to have in the first place, and fairly central to a lot of the ideas of what academia was meant to be to begin with. I don't like gatekeepers who don't have a really good reason to be such, like the trauma surgeon I mentioned in my classically unfair example in my previous post. When you combine it with the capability for easy exchange of information modern technology tends to give us, it's only a short trip to a whole crop of notions like folksonomies, the pursuit of databases of intentions, turning filtering techniques meant to catch spam into more sophisticated information-extraction methods, and any number of other things. Between the basic potential of these sorts of techniques and the willingness of so many pursuing them to share their research and tools all over the place (notice on that netiquette link above that one of the items was "share your expertise?"), I think it's a pretty exciting time to be an historian. Dealing with the mass of information currently sitting around due to electronic archiving's one thing; turning a lot of these tools on the stuff we've traditionally been condemned to looking through via microfiche readers is another entirely.

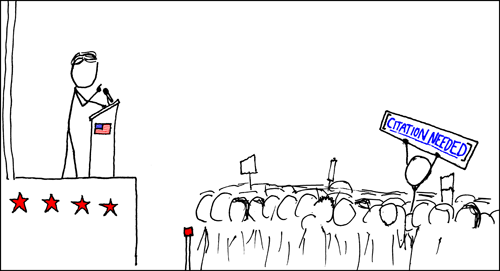

There are potential problems because of the Net and its cultures as a new base for scholarship as well, of course. Pretty much the standard debate to do with the Internet's implications for scholarship is the reliability/verifiability issue. This is something I've discussed before on this blog, and will probably continue doing so for some time; it's a pet topic of mine. Even a cursory reading of what I have to say over my time writing here should make it clear that I fall clearly in the "digital resources are useful and often reliable" camp - and, more to the point, that I despise the casual elitism which says one must need a tangible degree to even attempt to contribute to knowledge on issues. Despite that, I have my own problems with content on the Net and try to turn a critical eye onto it. Besides, the reliability issue isn't limited to history online. Academic history isn't infallible, sometimes having a real problem being uncritical about sources (as I found out during my undergraduate thesis, watching Thomas Szasz get invoked as a reliable source about mental illness several times). Public history has its own problems, as evidenced by controversial manipulation of exhibits at the War Museum or Smithsonian, or the mendacious silliness that is documentaries like The Valour and the Horror. There's differences of degree, but we do need to take the beam out our own eye on that account, no?

While I have a thorough appreciation for the attitudes of openness and general egalitarianism which were fundamental parts of digital culture since well before I started seeing it in the early nineties, I think they can be taken too far or too blindly at times. As an example, I'm part of that rather small subset of big-on-digital-stuff historians who doesn't like Wikipedia, or more to the point, the predominant intellectual culture on it. Jaron Lanier echoes a good chunk of my views in his essay on Edge (another site on my "everyone should go here sometimes" list), though he takes his objections a little further than I would by invoking terms like "digital Maoism." On a more scholarly and financial level, there's some debate over the issue of open-access content for traditional scholarship, with arguments ranging from the silly ("socialized science!") to more

These sorts of issues are going to be hovering around academia for some time. The "problem" is that they will do so regardless of whether academia goes down the path of open access or Wikiality or whatever else. Many institutions are cheerfully doing this kind of thing, with some advocates going so far as to make religious allusions through the use of terms like "liberation technology."Those who don't, however, will still have to respond to it in one way or another, as it becomes more and more obvious that simply saying "don't use online sources" is not an acceptable approach.

The interesting aspect of this shows up when we start to see a fusion of the different cultures I've been talking about lately. We've got that amateur culture, big on do-it-yourselfing and drawn into their various pursuits out of a genuine desire to do something; we've got the loosely meritocratic and not-so-loosely anarchistic elements of digital culture, with its appreciation of openness in design or knowledge and growing use of hugely collaborative projects; we've got the traditional academy, feeling around the edges of the potential of this merger. Of course there's room for uneasiness between the three elements, but at their heart all three are (in theory) built around an appreciation for knowledge and ability.

[1] - Google has since largely revived Usenet with its establishment of Google Groups a few years ago (and the newsgroup links are courtesy of them); a chunk of the "original" Internet is once again out there, active, vibrant and wasting bazillions of man-hours per day. Huzzah!

[2] - This image from Wikipedia's (I know, I know) article on Usenet, which illustrates the meanings of the different "hierarchies" of Usenet newsgroups, illustrates the alt.* hierarchy perfectly in the eyes of anyone who remembers the original thing.

[3] - "Anyone ... [who] knows Gene, Mark, Rick, Mel, Henry, Chuq, and Greg personally" is one of popular definition of such people. The Net used to be a small world.

No comments:

Post a Comment